f = open("test.txt")Bytes and Files

Seeing the world in ones and zeroes

IO Streams

Reading and Writing Files

Reading files

You probably have heard about files before. To read or write them from Python, we need the help of the operating system. The operating system will offer us a file handle1

In Python you obtain a file handle with the builtin open function:

We can now read from the file. We can choose to read all of its content, read it line by line, or even one character at a time:

three_characters = f.read(3) # read exactly 3 characters

one_line = f.readline() # read one line

all_lines = f.readlines() # read all linesNote that after something has been read, the cursor has moved on, and it will not be read again.

It’s important that you tell your operating system when you are done with the file, otherwise it might remain locked! You do this by closing the file handle:

f.close()Writing files

If we intend to write to a file, we need to specify it when we request the file handle by specifying “w” (for write) as our mode:

f = open("notes.txt", "w")We can then write to the file and close it again:

f.write("First line of text!\n")

f.write("Second line of text!\n")

f.close()Note:

.writewill write at the start of the file, not at the bottom.writewill not automatically write newline characters (unlikeprint).writewill return an integer: the number of characters it has written to the file stream

Prefer with open(…) as f

When a program, such as python.exe terminates, the operating system will reclaim all of its file handles. Nevertheless it is best practice to always close resources yourself.

This can be more tricky than you think to maintain in code. For instance, what if a contributor inserts a return between the opening an closing the file? We have already seen a solution for this problem in the form of try ... finally, since the finally block is always executed. But this can be a bit awkward, if you don’t plan to handle any exceptions. Thankfully there is a better way:

with open("file.txt", "r") as f:

content = f.readlines()

# start processing the contentThe special with ... as ... syntax is called a context manager. More about them later, for now all you need to know is that:

- The content manager will guarantee the file is always closed.

- If you’re not using a context manager for opening a file, you had better have a very good reason!

Working with stdout, stderr and stdin

stdout

Have you ever wondered how print works? Using print is a bit like writing to a file, except that it is printed to the terminal where you launched Python.

What happens behind the curtains is quite interesting. When Python starts up in your console, the operating system (OS) offers it a special file handle, stdout to which it can write. The OS will configure that file handle to print to the terminal, although users of your program may choose to redirect it to a file.

So when we call print, we are just writing to that special file handle stdout. In fact, this file handle is also accessible to us directly via sys.stdout and we can write to it directly:

import sys

sys.stdout.write("Hello!")Hello!6Note that when you write to sys.stdout directly, it doesn’t append a newline! In fact, it is a special convenience built into print to end every write with a newline. For instance, this will print a line of dots in about 3 seconds:

import time

for _ in range(80):

time.sleep(3 / 80)

sys.stdout.write('.')

sys.stdout.flush()

sys.stdout.write('\n')Here we had to add a line saying .flush here, otherwise Python would store our written characters internally in a buffer, until they are a bunch of them, and then write them to the stdout stream in one go.

stderr and stdin

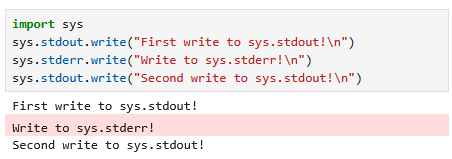

In fact, there exists another special file handle that is given to every program: stderr. For most programs running in a console, stderr is printed alongside stdout. Quite rarely, stderr will be shown differently from stdout, for instance this is the case in the Jupyter:

When Python encounters an unhandled exception, the information is by default sent to stderr. Finally there is a third special file handle stdin which can be used to read from the console:

line = sys.stdin.readline() # Will read until newline is pressed

print(f"Line entered:")So what does print do? Actually it is very similar to sys.stdout.write but print takes care of some extra stuff:

- It will convert its arguments to str first

- Add a newline character at the end (this can be suppressed with

print(..., end='')) - Supports writing multiple arguments in one go, with a space in between (or any character provided by

sep=...)

In fact, print can also write to other streams than sys.stdout by providing the file= keyword argument.

print("An error occurred", file=sys.stderr)

print("....", end="")

print("...", end="")

print("...")..........StringIO

Many functions are great for writing stuff to files. For instance, the library Pandas has great functionality for writing a dataframe to a csv file:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({"col1": [1, 2], "col2": [10, 20]})

df.to_csv("my_file.csv")But what if you want to capture the output instead for some further manipulation? You could write it to a file, and then read it but this is a can of worms: what should you name the file? How should it be cleaned up? What if you don’t have permission to write a file?

Python has a much better option with io.StringIO. This is an object which behaves just like a file handle, but it will simply keep everything that is written to it in storage until we retrieve it with .getvalue. Here is an example:

import io

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({"col1": [1, 2], "col2": [10, 20]})

storage = io.StringIO()

df.to_csv(storage)

df_as_csv = storage.getvalue()

print(df_as_csv),col1,col2

0,1,10

1,2,20

Redirecting stdout

If you want to redirect all your output to a file instead of to stdout, this is possible by assigning sys.stdout to a new value.

with open("output.txt", "w") as f:

sys.stdout = f

print("Function that does something")You should always set sys.stdout back its original value after your are done, because if your code later gets used in a larger piece of software, it it will be extremely confusing if you randomly change the output stream.

The original output stream is kept as sys.__stdout__ so you could simply assign sys.stdout = sys.__stdout__, but the recommended way is to use another context manager to redirect the stdout:

import contextlib

with open("output.txt", "w") as f:

with contextlib.redirect_stdout(f):

print("Function that does something")Now, everything in the inner block will see its output redirected to the file, and everything gets cleaned up nicely afterwards.

About bits and bytes

Computers think in binary

Everything on a computer consists of ones and zeroes! In practice we always use 8 bits at a time, this is called a byte. This is why an internet connection of 8 Mbps (megabit per second) as fast as a connection of 1 MB/s (megabyte per second).

A byte is usually represented with 2 hexadecimal digits:

bits, hex, dec

0000 = 0 = 0

0001 = 1 = 1

0010 = 2 = 2

...

1001 = 9 = 9

1010 = a = 10

...

1111 = f = 15So the byte 1010 0101 would be represented with A5. We will often write 0xA5 to clarify that we are using hex notation.

Hiermee komt ook een getal overeen:

1 x 1 = 1

0 x 2 = 0

1 x 4 = 4

0 x 8 = 0

0 x 16 = 0

1 x 32 = 32

0 x 64 = 0

1 x 128 = 128

Dus 0xA5 = 1 + 4 + 32 + 128 = 165The same sequence 1010 0101 also represents a single binary number. The number can be computed by summing the powers of two that have a 1:

1 x 1 = 1

0 x 2 = 0

1 x 4 = 4

0 x 8 = 0

0 x 16 = 0

1 x 32 = 32

0 x 64 = 0

1 x 128 = 128Dus 0xA5 = 1 + 4 + 32 + 128 = 1652.

Let’s explore this with Python:

0b10100101 # Create a number directly from its binary representation1650xa5 # Create a number from its hex representation165For Python, this is just a different way of addressing a number. In fact, we can easily mix all representations:

0x05 + 0b101 + 5 # hex + bin + dec15bytes and bytearray

How can we store raw bytes that don’t necessarily represent a number? Python offers two main datastructures:

- byte array objects

- bytes object (also called byte strings)

The relation between both is a bit like between a list and a tuple: a bytearray is like a list of bytes that can be modified in place, whereas a bytes object is static and cannot be modified.

To construct a byte array, we can start from a sequence of numbers between 0 and 255, each will represent a single byte:

arr = bytearray([165, 166, 164])Of course you can also use hex or bin if you prefer, or even mix these:

arr = bytearray([0xa5, 166, 0b10100100])If you try to put a number outside of the range 0-255 into a byte, Python will raise an exception:

arr = bytearray([1, 2, 256])--------------------------------------------------------------------------- ValueError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[9], line 1 ----> 1 arr = bytearray([1, 2, 256]) ValueError: byte must be in range(0, 256)

If you convert your bytearray to a list, you will just get the list of integers back. You can also grab one specific byte, and even modify it:

list(arr)[165, 166, 164]arr[1]166arr[1] = 0x00

arrbytearray(b'\xa5\x00\xa4')A bytes object, or byte string, is similar, but it cannot be modified after it’s constructed. You can construct one directly with the special b'...' syntax. The string \x.. is used to say: I want literally this byte, in hex:

byt = b'\xa5\x00\xa5'

bytb'\xa5\x00\xa5'byt[1] = 10--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[14], line 1 ----> 1 byt[1] = 10 TypeError: 'bytes' object does not support item assignment

Let’s print all possible bytes, 64 at a time. You should see something funny!

bytestring = bytes(i for i in range(255))

for i in range(4):

print(bytestring[64 * i:64 * (i + 1)])b'\x00\x01\x02\x03\x04\x05\x06\x07\x08\t\n\x0b\x0c\r\x0e\x0f\x10\x11\x12\x13\x14\x15\x16\x17\x18\x19\x1a\x1b\x1c\x1d\x1e\x1f !"#$%&\'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?'

b'@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~\x7f'

b'\x80\x81\x82\x83\x84\x85\x86\x87\x88\x89\x8a\x8b\x8c\x8d\x8e\x8f\x90\x91\x92\x93\x94\x95\x96\x97\x98\x99\x9a\x9b\x9c\x9d\x9e\x9f\xa0\xa1\xa2\xa3\xa4\xa5\xa6\xa7\xa8\xa9\xaa\xab\xac\xad\xae\xaf\xb0\xb1\xb2\xb3\xb4\xb5\xb6\xb7\xb8\xb9\xba\xbb\xbc\xbd\xbe\xbf'

b'\xc0\xc1\xc2\xc3\xc4\xc5\xc6\xc7\xc8\xc9\xca\xcb\xcc\xcd\xce\xcf\xd0\xd1\xd2\xd3\xd4\xd5\xd6\xd7\xd8\xd9\xda\xdb\xdc\xdd\xde\xdf\xe0\xe1\xe2\xe3\xe4\xe5\xe6\xe7\xe8\xe9\xea\xeb\xec\xed\xee\xef\xf0\xf1\xf2\xf3\xf4\xf5\xf6\xf7\xf8\xf9\xfa\xfb\xfc\xfd\xfe'Did you note that suddenly it starts printing the alphabet and some special symbols? That’s because these bytes are often used to represent letters in text files, so Python tries to be helpful and show the characters it represents.

These are the ASCII characters. For instance, the byte 41 means the letter A and so Python represents it a such.

b'\x41'b'A'This doesn’t really mean that those bytes actually are supposed to represent the character A! For instance these bytes may come from a music file and represent a pixel, which just happens to be represented by the same bits 0010 0001 that Python represents as the letter A.

Reading bytes

In Python we can easily read any file that is not a text file, just read its bytes! The syntax is simple:

with open('my_image.png', 'rb') as f:

content = f.read()The content is now a bytesobject that you can explore or one at a time or several at a time. Generally speaking there will have to be some convention on what the bytes actually mean.

Bytes to text and back again

When we write or read text, we are actually reading bytes, since it’s all a computer knows! This means there has to be some mapping which connects the bytes to which character it is supposed to represent. This mapping is called the character encoding. The simplest such encoding is ASCII, but it’s very limited.

One of the most popular character encoding is UTF-8. Here is how it works in Python:

"Bonjour Chérie".encode("utf-8")b'Bonjour Ch\xc3\xa9rie'b"\x42\x6f\x6e\x73\x6f\x69\x72".decode("utf-8")'Bonsoir'You can see that most characters get converted to the same bytes as in ASCII, so they look like “themselves” even when encoded as a byte. But the special character é is encoded by two bytes . This may surprise you, but utf-8 is a variable length encoding, so not every character will have the same number of bytes.

Different encodings will result in different bytes being produced:

"Bonjour Chérie".encode("Latin-1")b'Bonjour Ch\xe9rie'If your encoding doesn’t have a code for the character you are trying to use, you may expect an error:

"Bonjour Chérie".encode("ascii")--------------------------------------------------------------------------- UnicodeEncodeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[20], line 1 ----> 1 "Bonjour Chérie".encode("ascii") UnicodeEncodeError: 'ascii' codec can't encode character '\xe9' in position 10: ordinal not in range(128)

A frequent problem is that a person will encode something in one encoding, and another will decode it in a different encoding. If you see weird characters appearing in an otherwise normal looking text, this is probably what happened.

"Bonjour Chérie".encode('utf-8').decode('Latin-1')'Bonjour Chérie'Pathlib

The pathlib standard library offers a more object oriented alternative for the builtin function open. Its syntax is very simple:

from pathlib import Path

with Path("image.png").open('rb') as f:

content = f.read()These days the recommendation is that you mostly use pathlib.

Demo: reading PNG files

Next: Lesson 3: OOP I

Footnotes

In the unix world often called file descriptors but we will follow Windows terminology here.↩︎

In fact sometimes numbers are stored in the other order on a computer, so 165 would be stored as A5 instead of 5A. This is called the endianness. Although most processors these days use little endianness some protocols such as TCP/IP use big endianness.↩︎