class Animal:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

def __repr__(self):

return self.name

@classmethod

def from_dict(cls, d):

return cls(**d)

class Ship:

def __init__(self, name, mass):

self.name = name

self.mass = mass

def __repr__(self):

return self.name

@classmethod

def from_dict(cls, d):

return cls(**d)Design Patterns II

From ABC to Protocols

Introduction

In Design Patterns I, we explored the Gang of Four patterns and learned that many classic patterns are either obsolete in Python or already built into the language. We studied patterns like Factory, Composite, and Builder—understanding when to use them and when simpler Python idioms suffice.

Today we’re shifting gears. Instead of focusing on specific named patterns, we’ll explore three powerful concepts that fall under the broad umbrella of “design patterns”:

- Mixins: Sharing functionality across unrelated classes

- Abstract Base Classes (ABCs): Enforcing contracts while providing shared implementation

- Protocols: Defining interfaces without requiring inheritance

These aren’t traditional GoF patterns, but they’re essential tools in modern Python for creating extensible, maintainable code.

By the end of this lecture, you’ll use these concepts to implement the Game of Trust—a variant of the Prisoner’s Dilemma where different strategies compete against each other. You’ll design a system where new player strategies can be easily added and plugged into a game engine.

We won’t hand you the solution on a silver platter. Instead, we’ll guide you through the design process with hints and examples.

Mixins

Sometimes you want to add the same functionality to multiple unrelated classes without duplicating code. That’s where mixins come in.

The Problem: Duplicate Code

Let’s say you’re building a system with different types of objects:

Notice the duplication? Both classes have identical from_dict methods. If we had 10 classes, we’d repeat this code 10 times. Tedious and error-prone!

Let’s test them:

waf = Animal('Onzen Blakkie', 2)

boot = Ship('Ana', 2000)

print(waf)

print(boot)Onzen Blakkie

AnaAnd using the from_dict method:

waf_dict = {'name': 'Blakkie 2', 'age': 3}

Animal.from_dict(waf_dict)Blakkie 2The Solution: Mixin Classes

A mixin is a class that provides methods intended to be added to other classes via inheritance. The key characteristic: mixins don’t stand on their own—they’re designed to be mixed in.

class FromDictMixin:

@classmethod

def from_dict(cls, d):

return cls(**d)

class Animal(FromDictMixin):

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

def __repr__(self):

return self.name

class Ship(FromDictMixin):

def __init__(self, name, mass):

self.name = name

self.mass = mass

def __repr__(self):

return self.nameNow both classes inherit the functionality without duplicating code:

waf_dict = {'name': 'Blakkie 2', 'age': 3}

ship_dict = {'name': 'Titanic', 'mass': 52310}

print(Animal.from_dict(waf_dict))

print(Ship.from_dict(ship_dict))Blakkie 2

TitanicA More Interesting Example: PrintMixin

Let’s create a mixin that adds printing functionality to any container-like class. Here’s a first approach:

class PrintMixin:

def print(self):

object_container = self._container

for obj in object_container:

print(obj)

class Info(PrintMixin):

def __init__(self, messages, priority):

self.messages = messages

self.priority = priority

@property

def _container(self):

return self.messages

class People(PrintMixin):

def __init__(self, data, nr):

self.nr = nr

self.data = data

@property

def _container(self):

return self.dataThe mixin expects each class to provide a _container property. Let’s test it:

people = People(['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie'], 3)

people.print()Alice

Bob

Charlieinfo = Info(['System starting', 'Loading config', 'Ready'], priority=1)

info.print()System starting

Loading config

ReadyThis works, but there’s a more Pythonic way! Instead of requiring a _container property, we can make the mixin work with any iterable class:

class PrintMixin:

def print(self):

for obj in self:

print(obj)

class Info(PrintMixin):

def __init__(self, messages, priority):

self.messages = messages

self.priority = priority

def __iter__(self):

return iter(self.messages)

class People(PrintMixin):

def __init__(self, data, nr):

self.nr = nr

self.data = data

def __iter__(self):

return iter(self.data)Now the mixin is simpler and the classes are more Pythonic—they support iteration:

info = Info(['Today', 'no', 'class'], priority=-1)

info.print()Today

no

class# Bonus: since we implemented __iter__, we can use them in for loops!

for message in info:

print(f"Message: {message}")Message: Today

Message: no

Message: classBy convention, mixin class names often end with “Mixin” (e.g., FromDictMixin, PrintMixin). This makes it clear they’re intended to be mixed in with other classes, not used standalone.

Use mixins when:

- You want to share orthogonal functionality

- Multiple unrelated classes need the same utility methods

- There’s no “is-a” relationship between the classes

Use regular inheritance when:

- There’s a true “is-a” relationship (Dog is an Animal)

- You’re building a class hierarchy with shared state

- Subclasses extend or specialize the parent’s behavior

Abstract Base Classes (ABCs)

Abstract Base Classes provide a way to define interfaces when you want to enforce that certain methods must be implemented by subclasses, while also providing some shared functionality.

The Core Idea

The key insight with ABCs is this split of responsibilities:

- Library author: Provides partial implementation and defines which methods are required

- Library user: Must implement the abstract methods

- At runtime: The library’s concrete methods can safely call the abstract methods, knowing they’ll exist

This is different from regular inheritance (where the parent provides everything) and protocols (where the parent provides nothing).

Example: A Bank Account System

Let’s build a bank account system where we provide transaction processing, but let users implement the actual deposit/withdraw logic:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class BalanceInsufficient(Exception):

pass

class BankAccount(ABC):

"""Base class for bank accounts. Subclasses must implement deposit and withdraw."""

def __init__(self):

self._state = 0

@abstractmethod

def deposit(self, amount):

"""Add money to the account. Must be implemented by subclasses."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def withdraw(self, amount):

"""Remove money from the account. Must be implemented by subclasses."""

pass

def process_transactions(self, transactions):

"""Process a list of transactions. Provided by the ABC."""

for kind, amount in transactions:

if kind == 'deposit':

self.deposit(amount)

elif kind == 'withdraw':

self.withdraw(amount)

else:

raise Exception(f"Invalid transaction kind {kind}")

def can_afford(self, amount):

"""Check if the account has sufficient funds. Provided by the ABC."""

return self._state >= amountNotice what we’ve done:

deposit()andwithdraw()are abstract methods: subclasses must implement themprocess_transactions()andcan_afford()are concrete methods: they’re provided for free- The concrete methods safely use the abstract ones

Now let’s implement two different account types:

class MyBankAccount(BankAccount):

"""A responsible bank account that prevents overdrafts."""

def deposit(self, amount):

self._state += amount

def withdraw(self, amount):

if self.can_afford(amount):

self._state -= amount

else:

raise BalanceInsufficient("Balance not sufficient, transaction cancelled")

class Alameda(BankAccount):

"""A... creative accounting system. When you run out of money, just add more! 🎰"""

def deposit(self, amount):

self._state += amount

def withdraw(self, amount):

self._state -= amount

if self._state < 0:

# Oops, we're negative. Let's just... fix that.

self._state = 1000 # Customer funds? What customer funds?Let’s test them:

account = MyBankAccount()

transactions = [

('deposit', 300),

('deposit', 1000),

('withdraw', 800),

]

account.process_transactions(transactions)

print(f"Balance: {account._state}")Balance: 500What if we try to overdraw?

account = MyBankAccount()

transactions = [

('deposit', 300),

('withdraw', 800) # Trying to withdraw more than we have!

]

account.process_transactions(transactions)--------------------------------------------------------------------------- BalanceInsufficient Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[15], line 7 1 account = MyBankAccount() 2 transactions = [ 3 ('deposit', 300), 4 ('withdraw', 800) # Trying to withdraw more than we have! 5 ] ----> 7 account.process_transactions(transactions) Cell In[12], line 28, in BankAccount.process_transactions(self, transactions) 26 self.deposit(amount) 27 elif kind == 'withdraw': ---> 28 self.withdraw(amount) 29 else: 30 raise Exception(f"Invalid transaction kind {kind}") Cell In[13], line 11, in MyBankAccount.withdraw(self, amount) 9 self._state -= amount 10 else: ---> 11 raise BalanceInsufficient("Balance not sufficient, transaction cancelled") BalanceInsufficient: Balance not sufficient, transaction cancelled

The Alameda account, on the other hand, has… different rules:

account = Alameda()

transactions = [

('deposit', 100),

('withdraw', 200), # More than we have!

]

account.process_transactions(transactions)

print(f"Alameda balance: {account._state}") # Magically 1000! 🎩✨Alameda balance: 1000The power here is separation of concerns:

- The ABC author (you, in this case) handles the complex logic of processing transactions

- The ABC user just needs to implement the basic operations

- Everyone benefits from having the complex logic written once and tested thoroughly

This is particularly useful in frameworks and libraries where you want users to plug in custom behavior.

What If You Don’t Implement Abstract Methods?

Python won’t let you instantiate a class that doesn’t implement all abstract methods:

class BrokenAccount(BankAccount):

def deposit(self, amount):

self._state += amount

# Oops, forgot to implement withdraw!

account = BrokenAccount() # This will fail!--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[17], line 6 3 self._state += amount 4 # Oops, forgot to implement withdraw! ----> 6 account = BrokenAccount() # This will fail! TypeError: Can't instantiate abstract class BrokenAccount without an implementation for abstract method 'withdraw'

The error happens at instantiation time, not when you try to call the missing method. This is a form of early error detection. A decent type checker will even discover the error before running the code.

Real-World Example: collections.abc

Python’s standard library uses ABCs extensively in collections.abc. These define interfaces for various collection types.

For example, collections.abc.Mapping is the ABC for dictionary-like objects. To implement a complete mapping, you only need to provide three methods:

import collections.abc

# Let's see what we need to implement:

print("Abstract methods:", collections.abc.Mapping.__abstractmethods__)Abstract methods: frozenset({'__len__', '__getitem__', '__iter__'})Everything else comes for free! Let’s build a case-insensitive mapping:

class CaseInsensitiveMapping(collections.abc.Mapping):

"""A dictionary that treats keys as case-insensitive."""

def __init__(self, **kwargs):

# Store everything with lowercase keys internally

self._data = {key.lower(): value for key, value in kwargs.items()}

def __getitem__(self, key):

return self._data[key.lower()]

def __iter__(self):

return iter(self._data)

def __len__(self):

return len(self._data)Now watch the magic—we get lots of methods for free:

mapping = CaseInsensitiveMapping(Name="Alice", Age="30", City="Brussels")

# Access with any case:

print(mapping["name"])

print(mapping["NAME"])

print(mapping["NaMe"])

# We get these methods for free:

print("Keys:", list(mapping.keys()))

print("Values:", list(mapping.values()))

print("Items:", list(mapping.items()))

print("'city' in mapping:", 'city' in mapping)

print("'CITY' in mapping:", 'CITY' in mapping)Alice

Alice

Alice

Keys: ['name', 'age', 'city']

Values: ['Alice', '30', 'Brussels']

Items: [('name', 'Alice'), ('age', '30'), ('city', 'Brussels')]

'city' in mapping: True

'CITY' in mapping: TrueWe implemented three methods and got keys(), values(), items(), get(), __contains__, and more—all for free!

The collections.abc module contains ABCs for: - Iterable, Iterator - Sequence, MutableSequence (list-like) - Set, MutableSet - Mapping, MutableMapping (dict-like) - And many more!

Check the documentation to see what you need to implement vs. what you get for free.

Protocols

Protocols represent a different approach to defining interfaces: structural subtyping, also known as “static duck typing.”

The Core Idea

With protocols, we define what methods a class should have, but classes don’t need to explicitly inherit from the protocol. If a class has the right methods, it “implements” the protocol automatically.

This is the formal version of Python’s duck typing philosophy: “If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it’s a duck.”

From ABCs to Protocols

Let’s contrast ABCs and Protocols with an example. Here’s a Protocol:

from typing import Protocol

class Printable(Protocol):

"""Any object with a print() method that returns a string."""

def print(self) -> str:

...Now we can create classes that implement this protocol without inheriting from it:

class Knight:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def print(self) -> str:

return f'I am Sir {self.name}, knight of the realm! ⚔️'

class Priest:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def print(self) -> str:

return f'I am Father {self.name}, servant of the faith. 🙏'

class Wizard:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def print(self) -> str:

return f'I am {self.name} the Wise, master of arcane arts! 🔮'Notice: none of these classes inherit from Printable, but they all have a print() method that returns a string. They implicitly implement the protocol!

Type Checking with Protocols

Protocols are primarily for static type checkers (like mypy or Pylance). We can write functions that accept any Printable:

def announce(character: Printable) -> None:

"""Announce a character. Works with anything that has print()."""

message = character.print()

print(f"📢 {message}")

# All of these work:

announce(Knight("Lancelot"))

announce(Priest("Benedict"))

announce(Wizard("Gandalf"))📢 I am Sir Lancelot, knight of the realm! ⚔️

📢 I am Father Benedict, servant of the faith. 🙏

📢 I am Gandalf the Wise, master of arcane arts! 🔮The type checker will verify that each argument has a print() method. But if we pass something without the right method:

class Goblin:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

# No print() method!

# This will type-check fail (but might run anyway):

# announce(Goblin("Griznak")) # ❌ Type checker errorBy default, you cannot use isinstance() with protocols:

knight = Knight("Galahad")

isinstance(knight, Printable) # ❌ This fails!--------------------------------------------------------------------------- TypeError Traceback (most recent call last) Cell In[25], line 2 1 knight = Knight("Galahad") ----> 2 isinstance(knight, Printable) # ❌ This fails! File ~/.local/share/uv/python/cpython-3.13.5-linux-x86_64-gnu/lib/python3.13/typing.py:2117, in _ProtocolMeta.__instancecheck__(cls, instance) 2111 return _abc_instancecheck(cls, instance) 2113 if ( 2114 not getattr(cls, '_is_runtime_protocol', False) and 2115 not _allow_reckless_class_checks() 2116 ): -> 2117 raise TypeError("Instance and class checks can only be used with" 2118 " @runtime_checkable protocols") 2120 if _abc_instancecheck(cls, instance): 2121 return True TypeError: Instance and class checks can only be used with @runtime_checkable protocols

If you need runtime checking, you must make the protocol @runtime_checkable:

from typing import Protocol, runtime_checkable

@runtime_checkable

class PrintableRuntime(Protocol):

def print(self) -> str:

...

knight = Knight("Galahad")

print(isinstance(knight, PrintableRuntime)) # ✅ Now it works!TrueHowever, runtime checking is rarely needed. Protocols are mainly for static type checkers.

A More Practical Example

Let’s define a protocol for drawable objects in a game:

from typing import Protocol

class Drawable(Protocol):

"""Objects that can be drawn to the screen."""

def get_position(self) -> tuple[int, int]:

"""Return the (x, y) position."""

...

def get_sprite(self) -> str:

"""Return a string representation (simplified; normally an image)."""

...

def draw(self) -> None:

"""Draw the object."""

...Now we can implement various drawable objects:

class Player:

def __init__(self, x, y, name):

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.name = name

def get_position(self) -> tuple[int, int]:

return (self.x, self.y)

def get_sprite(self) -> str:

return "🧙"

def draw(self) -> None:

pos = self.get_position()

sprite = self.get_sprite()

print(f"{sprite} at ({pos[0]}, {pos[1]})")

class Tree:

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def get_position(self) -> tuple[int, int]:

return (self.x, self.y)

def get_sprite(self) -> str:

return "🌲"

def draw(self) -> None:

pos = self.get_position()

print(f"{self.get_sprite()} at ({pos[0]}, {pos[1]})")

class Coin:

def __init__(self, x, y, value):

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.value = value

def get_position(self) -> tuple[int, int]:

return (self.x, self.y)

def get_sprite(self) -> str:

return "🪙"

def draw(self) -> None:

x, y = self.get_position()

print(f"{self.get_sprite()} ({self.value} gold) at ({x}, {y})")Now we can write rendering functions that work with any drawable:

def render_all(drawables: list[Drawable]) -> None:

"""Render all drawable objects."""

for obj in drawables:

obj.draw()

# Create a scene:

scene = [

Player(10, 20, "Hero"),

Tree(15, 20),

Tree(15, 25),

Coin(12, 22, 50),

Coin(14, 18, 100)

]

render_all(scene)🧙 at (10, 20)

🌲 at (15, 20)

🌲 at (15, 25)

🪙 (50 gold) at (12, 22)

🪙 (100 gold) at (14, 18)The type checker verifies that every object in scene implements the Drawable protocol!

ABCs vs. Protocols: When to Use What

Both ABCs and Protocols define interfaces, but they serve different purposes. Let’s compare them directly.

The Key Difference

| Aspect | Abstract Base Classes | Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Inheritance required? | Yes, must inherit explicitly | No, just implement the methods |

| Provides implementation? | Yes, can provide concrete methods | No, purely interface definition |

| Enforcement | Runtime (can’t instantiate without implementing) | Compile-time (type checker only) |

Use isinstance()? |

Yes, naturally | Only with @runtime_checkable |

| Best for | Library authors providing functionality | Defining pure interfaces |

When to Use ABCs

Use Abstract Base Classes when:

✅ You’re providing shared functionality

class BaseProcessor(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def process(self, data):

pass

def run(self, data_list): # ← Shared implementation

return [self.process(d) for d in data_list]✅ You want runtime enforcement

# Can't instantiate without implementing abstract methods

processor = BaseProcessor() # ❌ Fails immediately✅ You’re working with inheritance hierarchies

class Animal(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def make_sound(self): pass

def breathe(self): # All animals breathe the same way

print("*inhale* *exhale*")✅ You need isinstance() checks

if isinstance(obj, collections.abc.Mapping):

# It's dict-like, we can use it safely

...When to Use Protocols

Use Protocols when:

✅ You’re defining a pure interface (no shared implementation)

class Comparable(Protocol):

def compare(self, other) -> int: ...✅ You don’t control the classes being used

# Third-party classes can satisfy your protocol

# without changing their code✅ You want structural subtyping (“duck typing”)

# If it has the right methods, it works!

def sort_items(items: list[Comparable]): ...✅ You’re focused on type checking

# Mainly for static analysis tools

def process(data: Serializable) -> None: ...Example: The Same Interface, Two Ways

Here’s how you’d implement the same concept with both approaches:

With ABC:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class LoggerABC(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def log(self, message: str) -> None:

pass

def log_error(self, message: str) -> None: # Provided by ABC

self.log(f"ERROR: {message}")

class FileLogger(LoggerABC): # Must inherit

def log(self, message: str) -> None:

print(f"[FILE] {message}")

logger = FileLogger()

logger.log_error("Something went wrong") # Uses the provided method[FILE] ERROR: Something went wrongWith Protocol:

from typing import Protocol

class LoggerProtocol(Protocol):

def log(self, message: str) -> None: ...

class ConsoleLogger: # No inheritance!

def log(self, message: str) -> None:

print(f"[CONSOLE] {message}")

def log_error(logger: LoggerProtocol, message: str) -> None:

logger.log(f"ERROR: {message}")

logger = ConsoleLogger()

log_error(logger, "Something went wrong") # Type checks![CONSOLE] ERROR: Something went wrongNotice:

- The ABC provides

log_error()as a convenience method - The Protocol just defines the interface; helper functions are separate

- If you’re writing a library and want to provide utilities → ABC

- If you’re writing a library and just need a contract → Protocol

- If you’re writing application code with type hints → Protocol

- If you need both, you can use them together! (Advanced topic for another day)

The Game of Trust: A Design Challenge

Now it’s time to apply what you’ve learned! We’ll design a system for the Game of Trust, a fascinating variant of the Prisoner’s Dilemma.

What is the Game of Trust?

The Game of Trust is based on the Prisoner’s Dilemma, one of the most famous problems in game theory. Here’s how it works:

The Rules:

- Two players face each other repeatedly

- Each round, both players simultaneously choose: Cooperate or Cheat

- The payoff depends on both choices:

- Both cooperate: Each gets 2 points ✨

- Both cheat: Each gets 1 point 😐

- One cooperates, one cheats: Cheater gets 3 points, cooperator gets 0 points 😢

The Dilemma:

- If you cooperate and your opponent cheats, you get nothing

- But if everyone always cheats, everyone loses in the long run

- Trust and cooperation lead to better outcomes, but they’re risky!

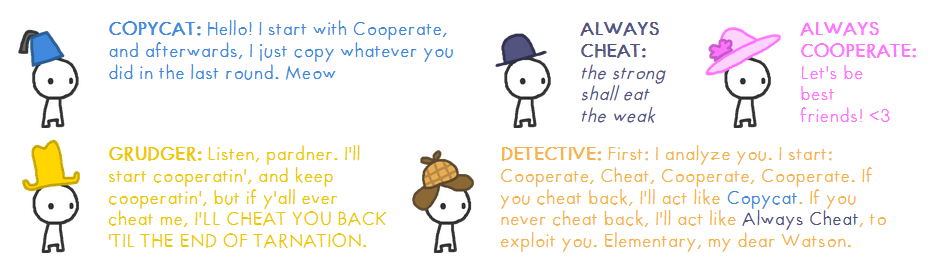

Here are some classic strategies:

- Always Cooperate: Trusting to a fault 😇

- Always Cheat: Ruthless and selfish 😈

- Copycat: Starts cooperative, then mimics opponent’s last move 🐈

- Grudger: Cooperates until cheated once, then always cheats forever 😠

- Detective: Tests the opponent first, then adapts 🕵️

For more background, check out this excellent interactive explanation or this video.

The Challenge

Your task is to design a system where:

- New player strategies can be easily implemented

- A game engine can pit any two players against each other

- The engine tracks history and calculates scores

- Extension: A tournament system that runs all strategies against each other

The key design question: Should you use an ABC or a Protocol?

Before looking at the hints below, spend 10-15 minutes thinking about the design:

- What methods should all players have?

- What information does a player need to make a decision?

- Should you provide shared functionality or just define an interface?

- How should the Game class work?

Sketch out a design on paper or in comments. Then use the hints to refine your solution.

What classes will be required at a high perspective?

There is going to be:

- a class named

GameorGameMasterwhich organizes rounds. - classes

AlwaysCheats,Detective, … for each player type.

How will these classes cooperate at the highest level? Start by thinking about the Game class.

Let’s think about the high level structure of the game first.

- Accept two players

- Run a specified number of rounds

- Get moves from both players

- Inform the players of the outcome

- Calculate and return scores

Structure:

class Game:

def __init__(self, player1, player2, rounds=10):

...

def play(self):

# For each round:

# - Get moves from both players

# - Calculate points

# - Store history

# Return final scores

...Payoff calculation:

from typing import Literal

Move = Literal['cooperate', 'cheat']

def calculate_payoff(move1: Move, move2: Move):

match (move1, move2):

case ('cooperate', 'cooperate'):

return (2, 2)

case ('cheat', 'cooperate'):

return (3, 0)

case ('cooperate', 'cheat'):

return (0, 3)

case ('cheat', 'cheat'):

return (0, 0)

case _:

raise RuntimeErrorAll player strategies need to make decisions. When do they need to make decisions? When do they receive new information?

There are essentially two time a player interacts with the game per round:

- Once, at the start, when they need to make a decision.

- Second, at the end of the round, when they are informed of their opponents decision.

Ask yourself the key questions from earlier:

Do you need to provide shared functionality? - Could be useful: a helper method like opponent_cooperated_last_round() - But most logic is strategy-specific

Will players inherit from your class? - If using ABC: Yes, they must inherit - If using Protocol: No, just implement the methods

Do you need runtime checking? - Probably not critical for this application

Recommendation: Either could work! - ABC if you want to provide helper methods - Protocol if you want more decoupling

For the solution below, we’ll use an ABC to demonstrate that approach. Feel free to try a Protocol instead!

Let’s put this idea in code:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Player(ABC):

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

# Subclasses might store arbitrary state here

pass

@abstractmethod

def next_move(self):

pass

@abstractmethod

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

# Investigate the opponents move

# The players can update their state to influence their

# next decision.

passLet’s implement the simplest strategies in this framework:

Always Cooperate:

class AlwaysCooperate(Player):

def next_move(self) -> Move:

return 'cooperate'

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

pass # Doesn't care what opponent doesAlways Cheat:

class AlwaysCheat(Player):

def next_move(self) -> Move:

return 'cheat'

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

pass # Doesn't care what opponent doesCopycat (slightly harder - needs to remember last opponent move):

class Copycat(Player):

def __init__(self, name):

super().__init__(name)

self.last_opponent_move = 'cooperate' # Start assuming cooperation

def next_move(self) -> Move:

return self.last_opponent_move

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

self.last_opponent_move = move # Remember for next roundNow try implementing Grudger and Detective yourself!

Here’s a minimal framework to get you started. Try implementing the missing parts yourself!

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from typing import Literal

Move = Literal['cooperate', 'cheat']

class Player(ABC):

"""Base class for all player strategies."""

def __init__(self, name: str):

self.name = name

@abstractmethod

def next_move(self) -> Move:

"""Return the next move for this player."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

"""Process the opponent's move from the last round."""

pass

def __repr__(self):

return f"{self.__class__.__name__}('{self.name}')"

class Game:

"""Runs a game between two players."""

def __init__(self, player1: Player, player2: Player, rounds: int = 10):

self.player1 = player1

self.player2 = player2

self.rounds = rounds

self.score1 = 0

self.score2 = 0

def calculate_payoff(self, move1: Move, move2: Move) -> tuple[int, int]:

"""Calculate points for both players based on their moves."""

match (move1, move2):

case ('cooperate', 'cooperate'):

return (2, 2)

case ('cheat', 'cooperate'):

return (3, 0)

case ('cooperate', 'cheat'):

return (0, 3)

case ('cheat', 'cheat'):

return (1, 1)

def play_round(self):

"""Play a single round."""

# TODO: Get moves from both players using next_move()

# TODO: Calculate payoff

# TODO: Inform both players of opponent's move using opponent_move()

# TODO: Update scores

pass

def play(self) -> tuple[int, int]:

"""Play all rounds and return final scores."""

for _ in range(self.rounds):

self.play_round()

return (self.score1, self.score2)

def print_summary(self):

"""Print game results."""

print(f"\n{'='*50}")

print(f"{self.player1.name} vs {self.player2.name}")

print(f"Rounds: {self.rounds}")

print(f"Final Score: {self.score1} - {self.score2}")

if self.score1 > self.score2:

print(f"🏆 Winner: {self.player1.name}!")

elif self.score2 > self.score1:

print(f"🏆 Winner: {self.player2.name}!")

else:

print("🤝 It's a tie!")

print(f"{'='*50}\n")

# TODO: Implement your strategies here!

class AlwaysCooperate(Player):

def next_move(self) -> Move:

# TODO: implement

pass

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

# TODO: implement

pass

class AlwaysCheat(Player):

def next_move(self) -> Move:

# TODO: implement

pass

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

# TODO: implement

pass

class Copycat(Player):

def __init__(self, name):

super().__init__(name)

# TODO: What state do you need to track?

def next_move(self) -> Move:

# TODO: implement

pass

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

# TODO: implement

pass

# Test your implementation:

# game = Game(AlwaysCooperate("Nice"), AlwaysCheat("Mean"), rounds=5)

# game.play()

# game.print_summary()Here’s a complete working implementation with multiple strategies. Study this after you’ve tried it yourself!

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from typing import Literal

Move = Literal['cooperate', 'cheat']

class Player(ABC):

"""Base class for all player strategies in the Game of Trust."""

def __init__(self, name: str):

self.name = name

@abstractmethod

def next_move(self) -> Move:

"""Decide next move. Called at the start of each round."""

pass

@abstractmethod

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

"""Process opponent's move. Called at the end of each round."""

pass

def __repr__(self):

return f"{self.__class__.__name__}('{self.name}')"

class AlwaysCooperate(Player):

"""Always cooperates, no matter what. The eternal optimist! 😇"""

def next_move(self) -> Move:

return 'cooperate'

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

pass # Doesn't care what opponent does

class AlwaysCheat(Player):

"""Always cheats, no matter what. Pure selfishness! 😈"""

def next_move(self) -> Move:

return 'cheat'

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

pass # Doesn't care what opponent does

class Copycat(Player):

"""

Starts by cooperating, then copies opponent's last move.

Also known as Tit-for-Tat. Simple but surprisingly effective! 🐈

"""

def __init__(self, name):

super().__init__(name)

self.last_opponent_move: Move = 'cooperate' # Start nice

def next_move(self) -> Move:

return self.last_opponent_move

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

self.last_opponent_move = move # Remember for next round

class Grudger(Player):

"""

Cooperates until cheated once, then cheats forever.

Holds a grudge like you wouldn't believe! 😠

"""

def __init__(self, name):

super().__init__(name)

self.been_cheated = False

def next_move(self) -> Move:

if self.been_cheated:

return 'cheat'

return 'cooperate'

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

if move == 'cheat':

self.been_cheated = True # Never forgive!

class Detective(Player):

"""

Starts with: Cooperate, Cheat, Cooperate, Cooperate.

If opponent never retaliates, always cheat.

Otherwise, play Copycat. Clever and adaptive! 🕵️

"""

def __init__(self, name):

super().__init__(name)

self.round_num = 0

self.opponent_ever_cheated = False

self.last_opponent_move: Move = 'cooperate'

def next_move(self) -> Move:

# First 4 moves: Test pattern

if self.round_num == 0:

return 'cooperate'

elif self.round_num == 1:

return 'cheat' # Sneak in a cheat!

elif self.round_num == 2:

return 'cooperate'

elif self.round_num == 3:

return 'cooperate'

# After testing: Did they ever retaliate?

if not self.opponent_ever_cheated:

# They never fought back! Take advantage forever

return 'cheat'

else:

# They fought back, so play nice (Copycat strategy)

return self.last_opponent_move

def opponent_move(self, move: Move):

if move == 'cheat':

self.opponent_ever_cheated = True

self.last_opponent_move = move

self.round_num += 1

class Game:

"""Manages a game between two players."""

def __init__(self, player1: Player, player2: Player, rounds: int = 10):

self.player1 = player1

self.player2 = player2

self.rounds = rounds

self.score1 = 0

self.score2 = 0

def calculate_payoff(self, move1: Move, move2: Move) -> tuple[int, int]:

"""Calculate points based on both players' moves."""

match (move1, move2):

case ('cooperate', 'cooperate'):

return (2, 2)

case ('cheat', 'cooperate'):

return (3, 0)

case ('cooperate', 'cheat'):

return (0, 3)

case ('cheat', 'cheat'):

return (1, 1)

def play_round(self):

"""Play a single round of the game."""

# Get moves from both players (simultaneously)

move1 = self.player1.next_move()

move2 = self.player2.next_move()

# Calculate payoff

points1, points2 = self.calculate_payoff(move1, move2)

# Update scores

self.score1 += points1

self.score2 += points2

# Inform players of opponent's move

self.player1.opponent_move(move2)

self.player2.opponent_move(move1)

def play(self) -> tuple[int, int]:

"""Play all rounds and return final scores."""

for _ in range(self.rounds):

self.play_round()

return (self.score1, self.score2)

def print_summary(self):

"""Print a summary of the game results."""

print(f"\n{'='*60}")

print(f"Game: {self.player1.name} vs {self.player2.name}")

print(f"Rounds: {self.rounds}")

print(f"Final Score: {self.score1} - {self.score2}")

if self.score1 > self.score2:

print(f"🏆 Winner: {self.player1.name}!")

elif self.score2 > self.score1:

print(f"🏆 Winner: {self.player2.name}!")

else:

print("🤝 It's a tie!")

print(f"{'='*60}\n")Let’s test our implementation with various matchups:

# Nice vs Mean

game1 = Game(AlwaysCooperate("Nice Guy"), AlwaysCheat("Mean Guy"), rounds=5)

game1.play()

game1.print_summary()

# Copycat vs Mean

game2 = Game(Copycat("Copycat"), AlwaysCheat("Cheater"), rounds=5)

game2.play()

game2.print_summary()

# Copycat vs Nice

game3 = Game(Copycat("Copycat"), AlwaysCooperate("Nice Guy"), rounds=5)

game3.play()

game3.print_summary()

# Grudger vs Detective (interesting!)

game4 = Game(Grudger("Grudgy"), Detective("Detective"), rounds=10)

game4.play()

game4.print_summary()

============================================================

Game: Nice Guy vs Mean Guy

Rounds: 5

Final Score: 0 - 15

🏆 Winner: Mean Guy!

============================================================

============================================================

Game: Copycat vs Cheater

Rounds: 5

Final Score: 4 - 7

🏆 Winner: Cheater!

============================================================

============================================================

Game: Copycat vs Nice Guy

Rounds: 5

Final Score: 10 - 10

🤝 It's a tie!

============================================================

============================================================

Game: Grudgy vs Detective

Rounds: 10

Final Score: 14 - 11

🏆 Winner: Grudgy!

============================================================

Notice how different strategies perform against each other!

Key design features:

- Players maintain their own state between rounds

- The

next_move()method is called to get decisions - The

opponent_move()method informs players what happened - The Game class orchestrates everything without knowing strategy details

Want to go further? Implement a tournament system that pits all strategies against each other:

class Tournament:

...Other extensions to try:

- Add “noise” (random chance of mistake)

- Variable number of rounds (players don’t know when game ends)

- Three-player variant

- Visualize game history with matplotlib

- Add more sophisticated strategies

Reflection

Think about what you’ve built:

- The Player ABC defines the interface and provides a clean base for strategies

- Each strategy is self-contained and easy to understand

- The Game class handles all the complex orchestration

- Adding new strategies is as simple as creating a new class

This is the power of good design! You’ve separated concerns, made the system extensible, and created clean abstractions.

Additional Resources

- PEP 3119 – Introducing Abstract Base Classes

- PEP 544 – Protocols: Structural subtyping

- Python

abcmodule documentation - Python

typing.Protocoldocumentation - collections.abc – Abstract Base Classes for Containers

- Type Hints in Python – Real Python tutorial

If you enjoyed the Game of Trust, explore:

- Axelrod Python library – Run tournaments with 200+ strategies

- Robert Axelrod’s book “The Evolution of Cooperation”

- The Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma

- The Evolution of Trust – Interactive game theory explanation

- Game Theory and the Prisoner’s Dilemma – Veritasium video

For more on design patterns in Python:

- Python Patterns Guide by Brandon Rhodes

- Design Patterns in Python – Refactoring Guru

- Python Design Patterns – GitHub repository with examples